Remembering Ken Squier: A Common Man Who Did Uncommon Deeds

Remembering Ken Squier: A Common Man Who Did Uncommon Deeds

Remembering the life and legacy of NASCAR Hall of Fame broadcaster and Thunder Road founder Ken Squier.

It was May 13, 1989. I was exactly one month shy of my sixth birthday, and my father had taken me to a car show in Barre, Vermont – an event to boost the looming opener for the stock car racing season at nearby Thunder Road International Speedbowl. The parking lot of the strip mall at which this particular show was being held was jam-packed with brightly colored racecars and star-studded drivers.

I can still smell that new racecar smell, fresh from the paint booth – back when they still used paint.

Dad had a box of flash cards and a pen, and he gave them to me to walk around and get autographs. I went straight to Ken Squier. I may have only been in Kindergarten, but I already recognized that he was important.

He was the guy on television, calling the races that featured Richard Petty and Bill Elliott and Dale Earnhardt. He was the guy in victory lane at Thunder Road, congratulating Greg “Burger” Blake and Rupert “Flipper” Erwin and “Grandpa” Jerry Driscoll. He was the guy on the local radio station, WDEV, which was located just a few miles away from where we lived.

He was the narrator of everything that gripped my attention.

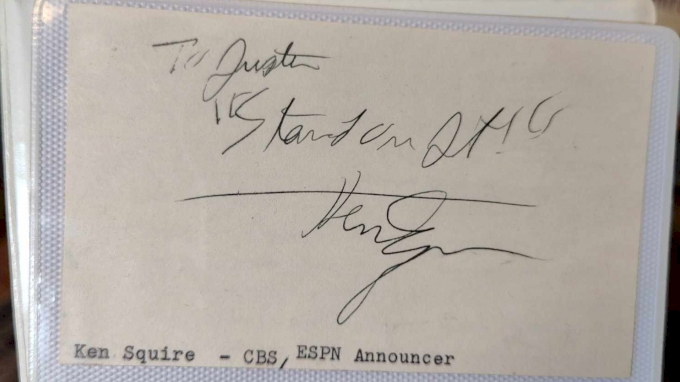

“To Justin – Stand on it!” he wrote.

Fast forward almost 35 years, and now I’m writing a memorial about the man. I remember that day, as clearly as if it was today. I still have those flash cards. That autograph is right here on my desk.

PHOTO: The note and autograph written by Ken Squier to Justin St. Louis in 1989.

The biggest bummer about the time that has passed in between that day and today is that I’ve had to do this type of thing a few times. Whenever someone around here dies, it’s my job to write the obituaries or deliver the eulogies. It’s a responsibility that I both love and loathe.

And every time I do it, I cuss Ken Squier a little.

You won’t be surprised by this: Ken loved to tell stories. He used words as an artist would handle a paintbrush. He was a minimalist when he could help it, carefully selecting his descriptors. He gave the reader, the listener – even the viewer – the tools to imagine their own scene.

Early in the 2003 season, I had blown the last motor in my four-cylinder rat trap of a racecar. I was 20 years old, broke, and feeling down about racing. Unannounced, I walked into the office of the great promoter Tom Curley – just seven miles from my childhood home – and told him that I wanted a job.

He sent me across Lake Champlain to Plattsburgh, N.Y., and Airborne Park Speedway. Like Thunder Road, he and Ken owned the place, but unlike Thunder Road, Airborne was in big trouble. There were only 50 racecars across five divisions, and maybe 250 fans on a good night. Tom told me that I would be writing the post-race press releases and helping out as the second announcer.

I had zero previous experience with either position, of course, and that’s probably why I went to Airborne and not Thunder Road. It wouldn’t be a big deal if I screwed it all up, because there was hardly anybody there listening anyway.

Except for one little hiccup, it was a perfect deal. That hiccup, for me, was Ken Squier, the voice of the Daytona 500, the curator of NASCAR’s in-car camera, the Hall-of-Fame announcer and multi-time national award winner for motorsports journalism.

Mr. Curley’s marching orders included Ken heading to The Big A to shadow me for a few weeks.

You read that correctly: Ken Squier (the man responsible for racing being on television and, therefore, in the American consciousness) was sent to shadow me (a destitute 20-year-old who was selling kitchen knives door-to-door and had never done this before) instead of the other way around.

Everything that Dave Moody says about his own training held true for me: Ken watched and listened on Saturday night, and then came the call to his office on Monday morning. He disemboweled me – or so it felt – telling me all the things that I did wrong on the microphone, stopping only briefly to highlight the one or two things that I did right by accident, before moving on to almost literally shred my press release (which, at Airborne in 2003, meant a hand-written recap sent to the newspapers and TV channels on a fax machine), line by line, with a pencil.

In both cases – both spoken and written – he emphasized brevity and word selection, and he demanded that I write down 10 different ways to say a given phrase. “Side by side” gets old after a while, so I had to work in “door handle to door handle” or “fender to fender” or even throw around some Vermont woodchuck slang and drop a heavily accented “side by each” on the crowd.

But above all, he drove the point home that stock car racing is hardly about the X’s and O’s as much as it is about the people. Walk the pits and talk to everyone that you can. Learn the histories and the hometowns. Figure out whose daughter is graduating high school next week, whose brother is fighting the war overseas, whose job schedule means that they may not make it in time for the heat race on double points night.

These are common folks doing uncommon deeds. They care, so I’d better care, too. Tell their story.

It was all overwhelming, but I was smart enough to shut up and take the notes. Within a year, I was hired full-time to run Curley’s PR department for Thunder Road, Airborne, and the American-Canadian Tour, and to be one of the announcers to replace the departing Moody.

I didn’t last too long in that office environment, but my work was solid, and I knew it. Ken’s guidance served me well, and it kept fans informed. I’ve never been a great announcer, but my writing really took off. I was careful with my words. I gave my readers enough of a setting for them to imagine being there.

I was hired to write for the three largest daily newspapers in Vermont, and to serve as a racing color analyst on Ken’s own WDEV radio station. I had more freelance work than I could handle. I became a publicist and announcer for Bear Ridge Speedway and eventually Devil’s Bowl Speedway.

Ken taught me how to not only tell the story, but how to look for it. Twenty years later, I’m still doing it with a podcast. My partner, Tom Corbett, and I only needed about 30 seconds to choose a name: Uncommon Deeds. Tom had worked for Ken for many years, too, and when we first met, our stories were practically identical.

As I have grown up, I’ve found that there are dozens of stories that parallel my own. Ask Mike Joy. Ask Dick Berggren. Ask Mark Garrow, Jackie Arute, Allen Bestwick, Troy Germain, Aaron Maynard, Joe Coss, Mike Massaro, Ozzie Altman, Todd Morey, Greg Titus…

We’re all here because of Ken’s guidance and advice. He taught us all. And since he taught me how to write so damn well, now I have to tell his story.

So here it is: Ken Squier lived in the same rural Vermont county his whole 88 years. He was the son of a radio station operator who announced his first stock car race at age 14 and promoted his first event at age 16. He built two race tracks and worked at dozens more. He founded the Motor Racing Network, which enveloped hundreds of radio stations nationwide. He convinced CBS to broadcast the 1979 Daytona 500 live on television, start to finish, and that single day changed NASCAR forever. He was a doting father and grandfather. He had a little sheep farm at his beautiful home in the hills of central Vermont. He was a television commentator for the Olympics. He loved music and served as chairman of the Vermont Symphony Orchestra. He acted in several movies and was elected to numerous halls of fame. He loved dogs. My god, did he ever love his dogs.

Above all, he cared. He cared about everything that he ever did. He cared about the people in his life, which must have numbered in the tens of thousands or maybe more. He cared enough about things he didn’t understand – like the Acapulco cliff diving championships on CBS Sports, for instance – that he devoted himself to understanding them so he could educate the masses and help them care, too.

And he cared enough about a kid from the trailer park up the road that he turned him – me – into someone that racing fans could rely on to tell the story and get it right.

He was a common man who did uncommon – and extraordinary – deeds.